Christmas Eve 2024

Year C

Luke 2:1-14(15-20)

In the name of the God who was, who is, and who is to come.

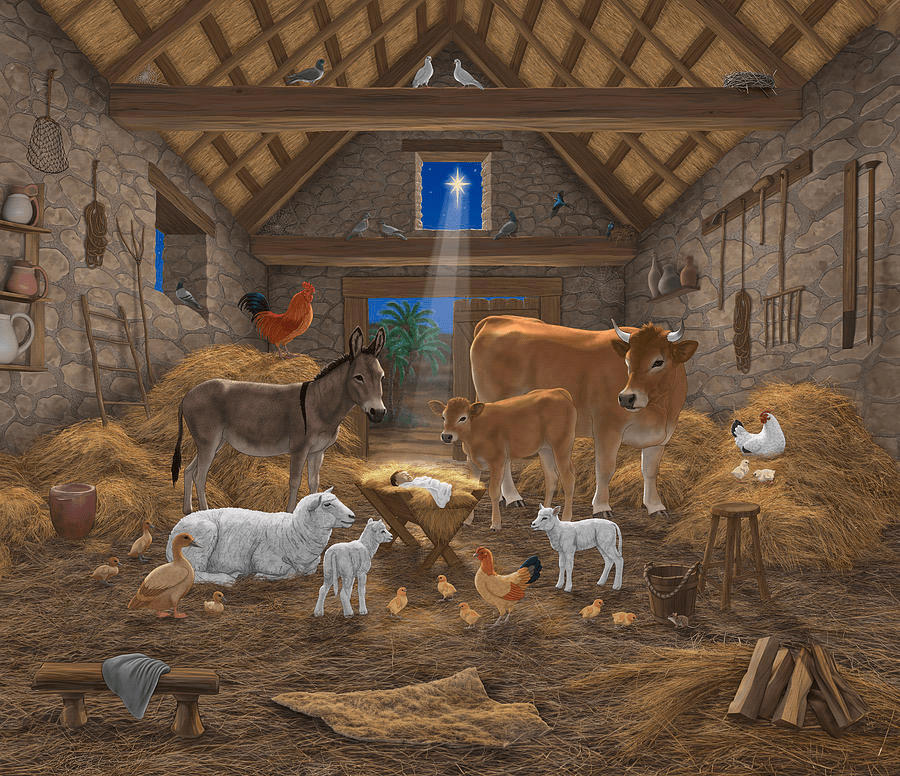

Tonight we celebrate the birth of Jesus. Tonight we light the Christ candle and the Holy Family has been placed in the nativity scene and the baby is laying in a manger. Many of us have nativity sets at home, too, and ours was handed down to us from my grandmother. It’s from the 1950s, but there are a few additional figurines from the World War II era that go on the mantle. As I was unwrapping the pieces to get them ready for tonight, I also discovered some ceramic figures my son had made in elementary school. Only Mary and Jesus have survived from our many moves since then.

You may not know it, but the nativity scene was a tradition that began nearly 800 years ago, in the Italian hill town of Greccio. It was there that St. Francis of Assisi in 1223, three years before his death, was inspired to celebrate the birth of Christ in a living creche: a hay-filled crib with a donkey and ox, and a baby and all the townspeople gathered around. He wanted to see, touch, and smell all there was to sense in the baby’s own awkward place, lying in an animal’s food trough. The event is considered to be the first living nativity. Elated from this experience of Christ come near, Francis preached to the crowds that gathered about the “Babe of Bethlehem” who was born a “poor King.”

For Francis that crib was a place where God’s humility poured forth in radical connection, the Creator of all things coming to dwell among the creatures of God’s own creation. To set a vision of the Christ Child among animals was not simply a nice medieval morality play, a faith-filled entertainment based on questionable details of Christ’s birth. Francis’s imagination followed the implications of Christ’s birth to include the animals that, though not mentioned in the scriptural accounts, were inevitably there, perhaps too obvious to even mention. Maybe a shepherd even brought a lamb as an offering. To make other creatures visible was to broaden the view of Christ’s coming into the world, a God-With-Us moment that extended God’s being-with beyond the bounds of the human. God was incarnate in the very microbes of all creation shared between animal, human, and dirt.

In The Christian Century this month, Ragan Sutterfield, an episcopal priest in Little Rock, Arkansas, writes about these microbes in the manger, organisms so fundamental to our existence that microbiologist Paul Falkowski has called them “life’s engine.” “Alongside nematodes and fungi, they are what enable plants to grow and flourish and dead things to return to the soil. But they exist on us and inside us as well. Both humus soil and human beings are alive with an abundance of creatures.”

“Humans are not only externally dependent on relationships with other creatures, but also internally,” writes theologian Hannah Malcolm, “in the very meaning of what it is to be a body, and, by extension, what it is for us to be human.” This truth leads us to radical possibilities for our understanding of Christ among us. As Malcolm puts it, “if it is true that to be human is to be microbiome, it was certainly true of the incarnate Christ.” Children playing in the dirt aides their well-being and so it was for Jesus, too! The soil is a source of many of our essential bacteria. From the garden we carry those creatures that help us live into health.

I’m not saying this so you’ll go home and put away your bleach spray, but I am making a point about our interconnectedness with all of creation. And I find this design of creation to be at the center of the story of the birth of Jesus.

It has long been understood that for God to become incarnate means that God not only took on human flesh but became entangled with the creation itself. Birth is a moment of separation and connection. This life that was wholly dependent upon its mother, fed in her womb, built by the foods she ate from the earth, now comes into its own. The infant, of course, is still deeply dependent. But from that moment of birth—for the first time—it takes on a reality in which its care is widened to a larger community. Another woman could now nurse this baby. Any man could now hold it and rock it to sleep.

In those first moments of delivery and its aftermath a child joins with the wider life of the creation. It is in delivery that the first significant inoculation of bacterial life begins. From the birthing, to the mother’s milk, and all the family and friends that hold and kiss the baby, it all helps to populate the microbiome of the child. From the instance of birth, we are connected to the earth and to one another. Basically, we need each other for our development beginning at birth. The connection of creation and community. It is vital not only to our physical well-being, it is vital to our spiritual, mental, and social well-being.

God locating Godself into human history has been a scandal throughout the ages with philosophers contending that the finite is not capable of the infinite. Modern humanity seems to think that if God is revealed at all, and for many that’s a big “if,” then at best it is through universal truths and principles, not particularly in space and time and a body. But you see, God has created us to be interdependent, not only with each other, but all created things. We simply cannot exist without each other, germy as that may seem.

We get sick, individually and as a community, not because we invariably ingest dirt, but because the microbes and bacteria get out of balance. So, we have to tend to our health. Likewise, a community gets out of balance and starts fighting with itself like our bodies will fight off bacteria that gets carried away inside our system. We have to work at staying in balance with one another. We are human probiotics for each other. Just sterilizing our world or getting rid of the bacteria is not helpful. We remain unhealthy if we do that.

Jesus entered into this world to bring it back into balance. And he didn’t do so with weapons or a strategic plan or a convenient way to make things logical for the philosophers and rational for the thinkers. God has a counterargument for the debaters: this decisive act of revelation and reconciliation was not an announcement of universal principles or truths; instead it was a baby. In all the messiness of birth, bacteria and blood, being held and kissed by both his father, the shepherds who probably hadn’t had a bath, and the angels, Jesus, came from the divine and immediately started mixing with humanity and all its dirt.

When Mary bore this baby, she shared all the teeming creatures of life’s engine, microbes and mitochondria, and Jesus shared his. Jesus enters our humanity to dwell in us as the divine and we share our humanity with Jesus. As do the oxen, the sheep, the hay, and the earth. The incarnation of God now dwells not only among us, but in us. Making us one with God, and one with each other. Maybe that is why the adult Christ taught us to love our enemies because we are so intrinsically connected that we are also loving ourselves. And we have become so disconnected from ourselves that we become diseased, revile and turn our backs on those we think are “others,” strangers in our midst. But they are not. We would do well to sit and think about that in the coming year. Those we send away, those we put away, are part of you and me. And Jesus has come to bring us back in physical and spiritual microbiological balance, to help us remember that God has by design made us to be connected to each other. We cannot be healthy and whole apart from one another. So as we place the baby Jesus in the manger this night, let us gaze on that nativity scene and all that have gathered around the manger and remember that everything, every creature, and every person, shares life and is the reason that baby is lying there in the first place.